Tim Olsen on getting out from under the shadow of his famous father John: 'He’s not a demigod'

The Guardian 10 November 2020

Susan Chenery

_view full article online

John Olsen’s Australian landscapes captured the world’s imagination but to his son the artist was akin to a deity – until he wasn’t

Where there is artistic acclaim there is often collateral damage. History is littered with redundant muses, discarded partners, children left behind. It can take a certain ruthlessness to live for art, in a heightened state of intensity, making it the only thing that matters.

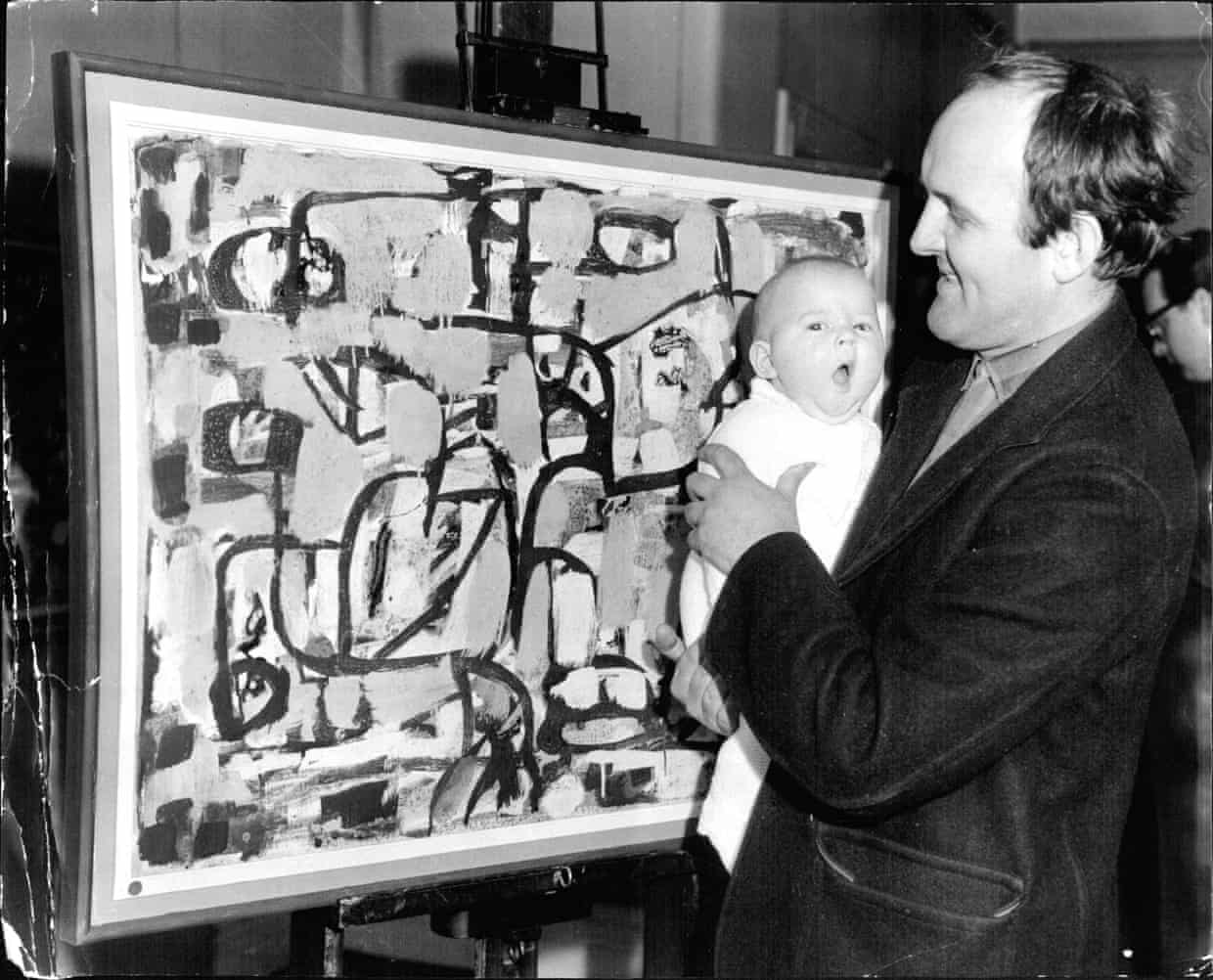

In the 60s the art critic Robert Hughes described John Olsen as a person who “disregards what matters to others, the things in between”. For Olsen’s son, Tim, his father’s painting was “a crucible undisputed in our house”. The art came first; an absolute compulsion for the artist, and the family revolved around it. “We protected it like a ritual flame that had to be relit each morning,” Tim writes in his newly published memoir, Son of the Brush.

Tim and his younger sister, Louise (known these days as one of the artists behind the hugely successful homewares and jewellery label Dinosaur Designs), grew up with the smell of gum turpentine, almost inside the great works that now hang in state galleries. “Dwarfed by canvases that loomed like vast apostles,” Tim writes.

Described by many as Australia’s greatest living artist, John Olsen, at 92, is still painting large-scale canvases at his home in the New South Wales southern highlands. To young Tim, his father was a deity, a sun king, whom he idealised. But he also instinctively understood, as he writes in his memoir, that “I would never have that luminescence. Strong sunlight casts a long shadow.”

Tim’s mother, Valerie Strong – “interesting, gentle and loving”, according to John’s biographer Darleen Bungey – had been a married art student when she came under the magnetic pull of Olsen. She gave birth to Tim two weeks after she married the artist in 1962.

Tim’s mother, Valerie Strong – “interesting, gentle and loving”, according to John’s biographer Darleen Bungey – had been a married art student when she came under the magnetic pull of Olsen. She gave birth to Tim two weeks after she married the artist in 1962.

Tim’s early years were spent in a fisherman’s cottage at Watsons Bay, in Sydney, with his parents. His father would take him for a swim every morning and meet the fishing boats. (To this day, Tim remains a morning ocean swimmer.) There the garrulous, passionate John, a man of large appetites, would cook great pans of paella and entertain his friends – Russell Drysdale, Donald Friend, Barry Humphries, Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd among them.

Speaking to Guardian Australia by phone, Tim says of his father: “He often says to me when you look at a great painting you should be able to taste it.” John was, he says, the centrifugal force. Sleeping under dinner tables with these “magnificent people” in full flight, the Olsen children were steeped in art from birth: “The objects around us educated our subconscious as much as what we were later taught.”

Those early days were so perfect, Tim writes, that “this perception infected everything that came after, setting the summit of life far too high”.

In 1969 the family moved to Dunmoochin, an artists’ community in Victoria owned by the painter Clifton Pugh, where sexual liberation was in full swing. John painted a new landscape in a new palate alongside Pugh and Fred Williams. But for the children the commune was damaging. Tim writes that he saw “things that a child really should not see”, including his father’s sexual escapades with people other than his mother. He also saw the petty jealousies. After his father won the Wynne prize, Tim was ambushed by eight kids who urinated on his face saying: “You and your Dad are fucking arseholes.”

Through the pain of her husband’s infidelities, Valerie continued to paint. “When I look at the difference between my father’s work and my mother’s,” recalls Tim during our conversation, of John’s great topographical works, “Dad liked to get above the landscape and say, ‘Hey, this is my land.’ You know, that’s an ego thing. It’s male-dominated, conquering. My mother would creep in like a gumnut baby and look around the bush in a way that she belonged to it.”

After 20 years of marriage, John left a devastated Valerie, moving to Clarendon in South Australia for a doomed and turbulent marriage to the artist Noela Hjorth. “He just disappeared on us,” Louise has said. Tim says that in these years, John was “invisible”.

When he later married Katherine Howard in 1989, his children could not get him on the phone. Tim recalls his mother phoning his father in a state of desperation about Tim’s out-of-control drinking and his urgent need of rehab. Katherine told her: “Valerie, you’ve had your settlement and whatever’s wrong with him he brought upon himself,” and hung up. “She kept my father in the dark,” Tim says.

Although Tim was rejected and hurt, his compass always pointed to the magnetic pull of his father. It wasn’t until he was in his mid 40s – after more than two decades of obsessing, flailing, anger at feeling “unheard”, feelings of unworthiness and, finally, recovery from alcoholism – that he finally saw his father for who he is. “I realised he’s just a human just like me,” Tim says. “He’s not a demigod. He’s not someone to define myself by any longer. He was born with incredible talent but everybody has character defects.”

Although Tim was rejected and hurt, his compass always pointed to the magnetic pull of his father. It wasn’t until he was in his mid 40s – after more than two decades of obsessing, flailing, anger at feeling “unheard”, feelings of unworthiness and, finally, recovery from alcoholism – that he finally saw his father for who he is. “I realised he’s just a human just like me,” Tim says. “He’s not a demigod. He’s not someone to define myself by any longer. He was born with incredible talent but everybody has character defects.”

Son of the Brush is about that love in all its degrees. With the help of sobriety, he sees John’s abdication from his children’s lives as a positive thing. “Instead of blaming Katherine like I used to, I want to thank her,” Tim says now. “With Noela and Katherine extracting him from our lives we realised that we could not expect to rest on the laurels of him, or that he was going to get us what we wanted in life. We would have to work.”

Tim tried to follow his father’s footsteps as a painter. “I did not have the calling,” he writes. “I was diligent but without that essential spark.” Instead he became a high-profile art dealer, with galleries in Sydney and New York. And, as no one could understand his father’s work the way he does, he is also John’s dealer. To avoid nepotism, John refused to exhibit with him until he had established himself with a stable of artists.

“He prevented me from behaving like an entitled person,” Tim says. “I am glad I had to jump through those hoops.”

After a 27-year marriage to Olsen, Katherine died of a brain tumour in 2017. Her death precipitated new tumult: last year the family were splashed across national newspapers when John sued his stepdaughter, Karen Mentink, for convincing her dying mother to transfer $2.2m to her. Justice Sacker found Mentink had used “unconscionable conduct or undue influence” to procure the payment, a judgment upheld on appeal. In the book, Tim writes: “Dad feels now that Katherine betrayed his trust and that, blinded by love, he let her go far beyond what he should have.”

And so to love. After decades of distance, of absence, comes John’s rapprochement with his children: amends, forgiveness, peace. “The love is back,” says Tim. His children had worshipped him, Louise told Bungey; that love never went away.

The Olsens are now cocooned like they were in Watsons Bay all those years ago, and this unexpected time together is precious. Cooking together, reading, reciting poetry, making up for lost decades. Tim watches the football with his dad, Louise has taken up painting and turned a large room into a studio. John pops in and out giving feedback – he can be “brutal”, Louise has admitted. Although she had always privately drawn and painted, she had hesitated from showing her work for fear of being compared with her parents. In March she had a sell-out show at her brother’s gallery.

The Olsens are now cocooned like they were in Watsons Bay all those years ago, and this unexpected time together is precious. Cooking together, reading, reciting poetry, making up for lost decades. Tim watches the football with his dad, Louise has taken up painting and turned a large room into a studio. John pops in and out giving feedback – he can be “brutal”, Louise has admitted. Although she had always privately drawn and painted, she had hesitated from showing her work for fear of being compared with her parents. In March she had a sell-out show at her brother’s gallery.

“It’s coming full circle,” Tim says. For the Olsens, he writes, “The paint will never be quite dry.”